Metal detecting holidays in England with the World's most successful metal detecting club.

Twinned with Midwest Historical Research Society USA

|

Mass

Bruce's axe head hoard - report |

|

|

Finally purchased by Colchester Museum in 2006 for display This find is

truly a find of a lifetime for me due to it's rarity. For any that don't

know, to find an axe head while detecting in the UK is extremely rare,

to find 7 whole ones, 2 pieces, 3 ingots and a big pile of slag is unbelievable.

After I pulled

it out, I called Linda on the walkie talkie to tell her what I had found.

She was about a mile away in a different field and said that was great

and we chatted a bit. Finally I filled back the hole, got up, rescanned

the hole and bang, still another signal. Ok, redig it out, get down

to that level

We sat there

for quite a while in awe just looking at these things. Someone mentioned

a story about how these peddlers would go into these villages to sell

their wares and most of the time would bury what they had so they didn't

get killed by peasants to steal their goods. They would go into

Well, now the

museum shows up along with some nasty weather. Anyone that has detected

in England knows why they call this weather "bootsticking weather",

the ground has alot of clay and this stuff just sticks to everything

it touches. So out come 2 women from the museum, one of them in a dress,

hoofing across this mud pit By the time they get out to where we are,

it is snowing, hailing and raining, along with 50 mph winds. Oops They

get out to where we are and take all there measurements and coordinates

etc... As we are bagging up the slag, another really small axe head

is found mixed in, which brings the total to

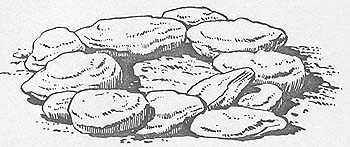

These are the 3 ingots, 2 small ones and a big one. The big one must have weighed 20 pounds.

The one on the left was the smallest one (till the even smaller one was found afterwards), the one on the right was the biggest and was made with a socket on each side to insert the wood into so that it wouldn't twist.

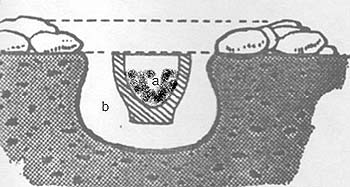

This one shows the depth of the hole. When I hit bottom, it was 33 inches deep!

Ok, thats it on the actual

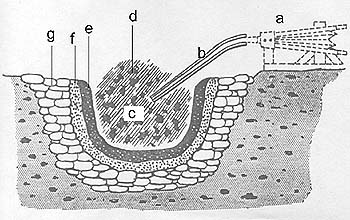

story, the rest is some research Here is some info on how they melted and made these. 1. The earliest furnaces

were mere camp fires: circles of stones which limited the fire place.

2. When people

discovered the benefits of copper and later bronze, attempts were made

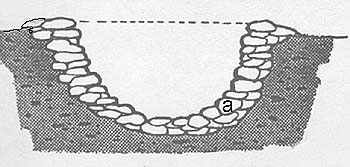

to smelt these metals. 3. One step

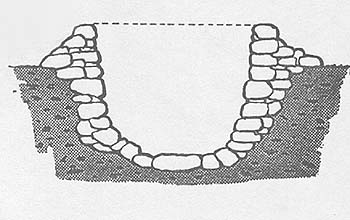

further, attempts were made to reach higher temperatures. Lining the

furnace with stones (a) could then better maintain the heat. 4. A higher

edge could also help in reaching a higher temperature. 5. This is a possible situation in which one could smelt the copper ores to win the copper. a. Bellows

The next 3 pics are of what the casting process would have looked like. The first one has 2 foot bellows that I guess would keep the fire hot enough.

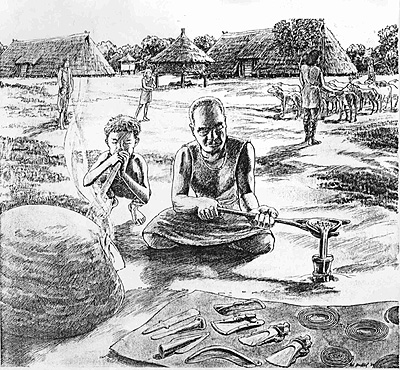

This one is an artists impression of a bronze age caster. Notice the tools laid out in front

This picture shows some molds of the axes, I really like this pic as it shows what the molds looked like and puts some perspective on everything.

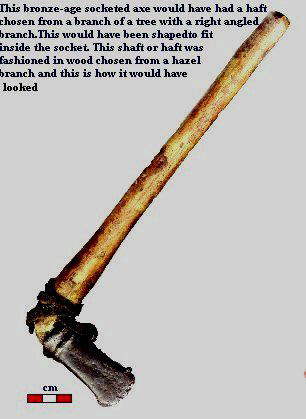

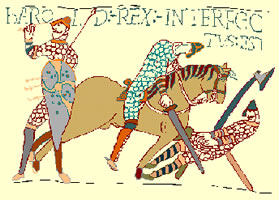

Last but not least, is how the wood was attached to these. This part of the article I got from the depot online magazine from an article that Charles in England wrote. The development of metal working was very gradual and involved experiments with alloys. It was found that the addition of 10% of tin to copper produced a bronze alloy capable of being cast in moulds to make tools with a more enduring cutting edge. Production was speeded up and tools and weapons of bronze became more common. The problem of securing a flat axe-head to its haft led to the development first of flanges, then of loops and sockets in the axe-head to give greater strength and firmness. The gradual improvement of the quality of the bronze alloy by the addition of lead in the later Bronze Age made it possible to produce buckets and cauldrons, giving better cooking facilities, as well as swords, shields and horse harness to advance the techniques of warfare. Much of our knowledge of metal working has come from the discovery of hoards of bronze weapons and ornaments, some of which are thought to be the stock-in-trade of itinerant metal workers.

Hafting. Many of the implements had wooden handles or hafts. These could be tied by thongs or cords to loop implements. Rivets and pegs were also used to secure handles. The type I used to secure the socketed axe replica was taken from a lilac tree and was shaped similar to a horses head handle of a walking stick, the handle proper being about 12" in length. The head was inserted into the socket. A leather belt was cut into 10" long thongs, 10mm wide to fasten through the loops to the handle itself. Hope that this wasn't too

long and boring for you. Joka

|